Introduction,

New York, which is widely recognized as a global metropolis, has a rich and varied character that is admired worldwide due to its numerous boroughs and neighborhoods. The city that never sleeps is also always changing, shaped by over two centuries of economic cycles and the trends in architecture and urban planning that go along with it.

The emergence of a super-rich enclave in Manhattan, however, is one noteworthy recent development. This new breed of residences, with their breathtaking vistas, opulent interiors, many facilities, and eye-watering price tags, are only for those with tens of thousands of dollars to spend. However, how did this region develop?

What caused it to flourish in this specific district? How were planning restrictions handled, and how did engineers make it profitable to build such little parcels of land? This is the backstory of “Billionaire’s Row” in New York.

Manhattan Island is currently one of the most densely inhabited places on Earth due to its enormous popularity and extremely constrictive geological setting. Developers have been vying for space here for decades, juggling their demands for profit with the municipal planners’ specifications and consideration for the many neighborhoods’ unique identities on the island.

These discrete neighborhoods influence the city we live in today, from the upscale financial districts of Midtown and Lower Manhattan to the upscale neighborhoods of Chelsea, Greenwich, and Soho, as well as the upscale residences on the Upper East Side. Planning restrictions have made it extremely difficult to rebuild any large areas in established residential zones, even if they have also served to clearly define the characteristics of these many neighborhoods.

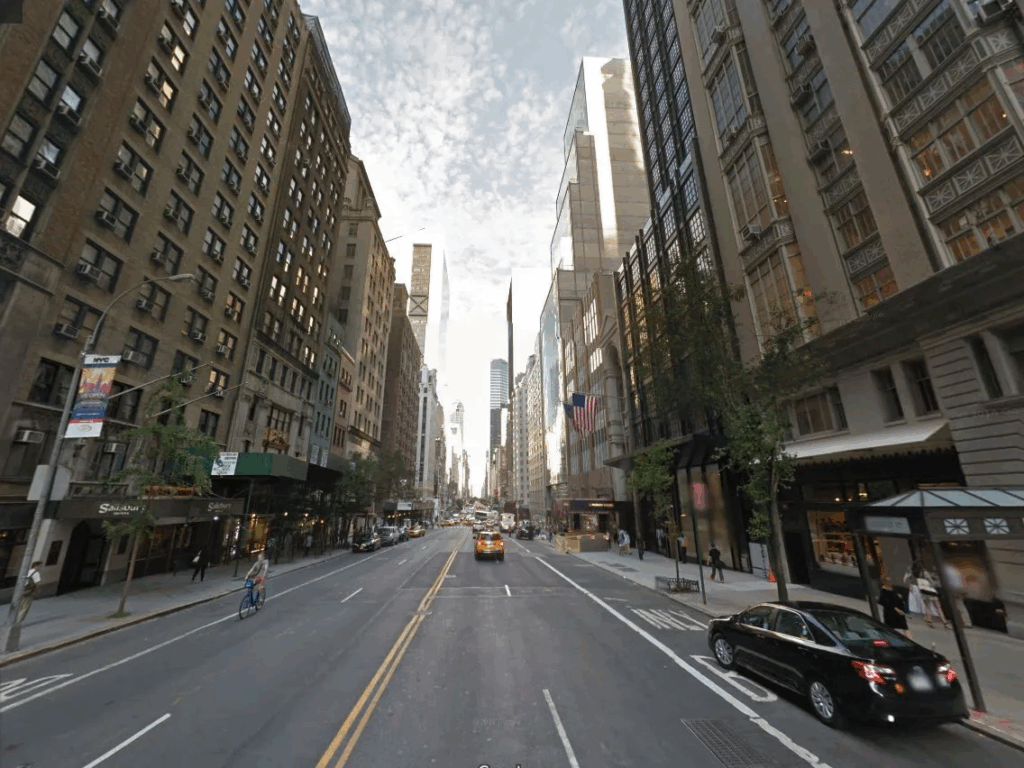

Developers have started to look for suitable sites in commercial districts as a result of Manhattan’s growing attractiveness and the growing demand for luxury homes in NYC. The Midtown streets between Park Avenue and Columbus Circle, which are located directly southwest of Central Park, have always exuded a sense of distinction.

The region is particularly attractive to high-end residential developers since it is home to the famous Plaza Hotel, the Russian Tea Room, Carnegie Hall, and the coveted Fifth Avenue.

Over the past ten years, several noteworthy projects have surfaced in this region, particularly along 57th Street, earning the neighborhood the moniker “Billionaire’s Row.” Following the completion of One57 in 2014, 432 Park Avenue opened in 2016, and 53 West 53rd Street, 111 West 57th Street, and Central Park Tower were subsequently developed.

With addresses in some of the city’s most sought-after streets, proximity to upscale retail establishments, and distinctive views of Central Park, these developments provide a high level of luxury. Avoiding Manhattan’s co-operative arrangements, where purchasers normally acquire stock in the company that owns a property in return for the sole use of one of its units, is an additional advantage. These agreements require financial information to be disclosed, which isn’t always desirable to the extremely wealthy.

Developers have received returns of several billions of dollars on these schemes thus far, with unit sale prices ranging from tens of millions to hundreds of millions. But it’s difficult to construct here.

Commercial developers must maximize floor space to recoup their site acquisition and development expenses.

Because of this, they frequently design buildings that extend to the site’s borders. At the same time, all plans have to follow the stringent Floor Area Ratio (FAR) planning laws in New York, which regulate a structure’s height concerning the area of its site.

Developers buy the air rights from nearby properties and successfully stack them onto their plots in order to get over this possible barrier. Developers and residents of their buildings are guaranteed light and unobstructed views out, and city planners are protected from potential overdevelopment of nearby properties.

The additional advantage of these agreements is that they help those selling their rights raise money so they can move forward with smaller-scale building projects on their property. Perhaps the best example of this idea to date is 53 West 53rd Street. Here, the current Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) sold the air rights over a portion of their estate along with a piece of land next to their main structure.

This made it possible to build the 53W53 skyscraper, which was designed by Jean Nouvel and raised money to renovate the museum.

Fortunately, the connection between the two buildings on the property has been preserved in Nouvel’s strikingly creative design, which complies with many zoning and setback restrictions, as well as in donor memberships at the museum for people who buy homes.

Developers have turned to their project teams to solve the problem of creating super-slender tower structures, which are defined as having a width-to-height ratio greater than 1:7. This is because they have such small sites, a strong desire to build high and maximize floor area, and the legal restrictions on doing so have been lifted.

Engineers have been able to improve the overall strength of their constructions and design flexibility by switching from steel to high-strength reinforced concrete. Super slender towers shift much of their remaining structure to the floor plate’s perimeter, eliminating the need for columns and maximizing utility within homes thanks to high-strength concrete cores that house their vertical access and service routes. Regarding 53W53 and the striking 432 Park Avenue,

However, even though the construction of these ultra-slender towers was made possible by high-strength reinforced concrete, additional engineering was necessary to ensure their stability at such extreme heights. 432 Park Avenue, which has a width-to-height ratio of 1:15, has double floor cutouts at 12-story intervals throughout its height, allowing powerful wind forces to pass through and around its extremely thin structure. This prevents areas of low pressure from being created on one side of the structure as air currents move around it, which could create repetitive, rhythmic suction forces that would cause the tower to sway towards its upper levels if left unchecked. We have used SimScale software to illustrate the impact of 432 Park Avenue’s design.

Through the Community account, users may test the platform for free and access hundreds of public simulations that encourage knowledge exchange and crowdsource recommendations. In order to counteract swaying motions where they start, 432 Park Avenue uses tuned mass dampers, which are extremely heavy devices hung in voids at the top of the building.

When it is finished in 2020, the 472-meter Central Park skyscraper will be the tallest building on Billionaire’s Row and the second-highest skyscraper in the US.

This development’s façade is varied throughout its height by combining an irregular profile with many setbacks, which disrupts wind currents and prevents the creation of coherent vortices and dominating wind loads that may arise.

Last but not least, the very slender and finely detailed 111 West 57th Street, which has a width-to-height ratio of 1:24, breaks up the façade homogeneity that might cause vortex shedding by gradually tapering over its 435-meter height.

Not only has New York’s billionaire’s row emerged and is still growing as a result of these remarkable architectural advancements, but a more widespread phenomenon of ultra-slim skyscrapers is also beginning to have an impact on other markets globally. These buildings in New York City, and their presence is exclusive to this period in the history of architecture on our planet.

Because of New York’s zoning regulations, its almost unparalleled attractiveness, its ravenous developers, and its technical prowess, billionaire’s row has emerged as the newest unique neighborhood.